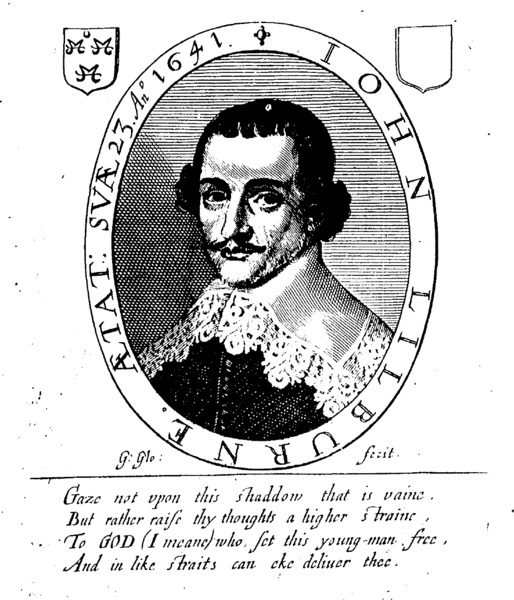

June and July are interesting months in the historical chronology of the Levellers. Three hundred and seventy two years ago next month sees the anniversary of the arrest of John Lilburne, the famous Leveller agitator, for the alleged slandering of William Lenthall, at that time the Speaker of the House of Commons. The grounds upon which the warrants were issued centred upon supposedly false accusations that Lenthall had been corresponding with Royalists. The fact that many of those within the English Civil War Parliamentary Movement, who were simultaneously members of the landed gentry and therefore represented the interests of wealth and privilege that had historically been aligned to the Crown, were ultimately seeking a compromise with the King and the establishment of a limited monarchy along modern constitutional lines, means that it is perfectly possible that these accusations were well founded. However, in the absence of hard evidence Lilburne had nothing to substantiate the claims that he had made and was therefore to find himself imprisoned.

That October, however, in spite of the gravity of what he had been accused of, Lilburne was to be released in the wake of a petition to the House of Commons which had been signed by over two thousand leading London citizens. This in itself would tend to suggest that many of the population, particularly among the limited classes who were at that time eligible to vote, not only shared his views but were willing to put their signatures to a document in order to defend them. Of further significance is the historic role of the London Citizenry in the crowning of each successive monarch in Anglo-Saxon times. Something that would feature much in the writings and discourse of many of those who were to become caught up in the Leveller Movement of which Lilburne himself was to all intents and purposes the founder. A fact that is evidenced by reference to the transcripts of the Putney Debates.

But this was not to be the end of the affair by any means. The following year, in June 1646 Lilburne was to find himself arrested and imprisoned again. This time for slandering the Earl of Manchester, whom he had accused of protecting an officer who had been charged with treason. In addition to this he had also referred to Manchester, who had been Lilburne’s former commander prior to the latter’s resignation of his commission upon refusing to sign the Solemn League and Covenant, a matter we shall look at in detail in a future post, both as a traitor as well as a Royalist sympathiser.

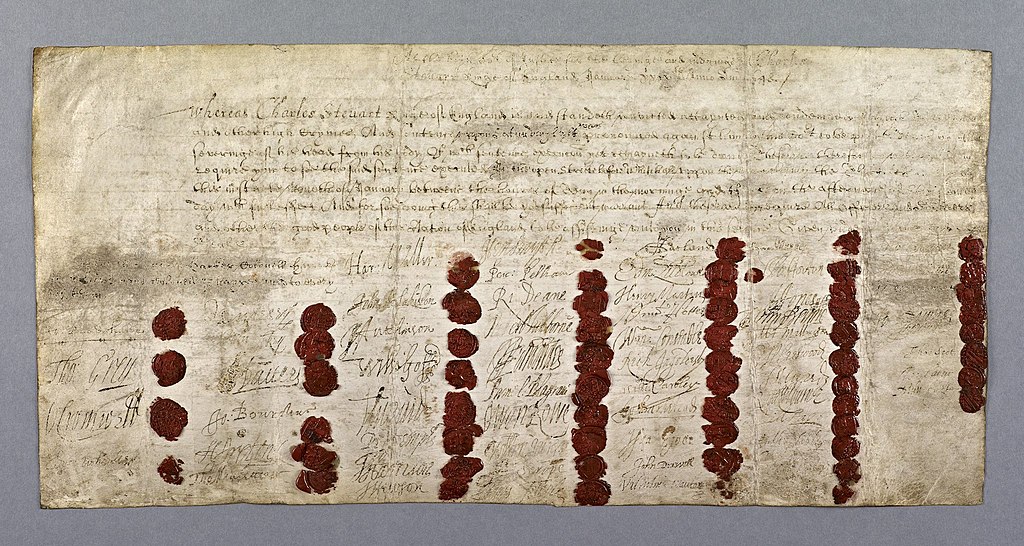

On the eleventh of July 1646 Lilburne was brought before the House of Lords, and following a short trial, sentenced to seven years imprisonment. The Judgement of the House of Lords, dated the same day as his trial, that of 11th July 1646, is transcribed in full below:

“It is to be remembered, that, the Tenth Day of July, in the Two and Twentieth Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King Charles, Sir Nathaniell Finch Knight, His Majesty’s Serjeant at Law, did deliver in, before the Lords assembled in Parliament at Westm’r, certain Articles against Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne, for High Crimes and Misdemeanors done and committed by him, together with certain Books and Papers thereunto annexed; which Articles, and the said Books and Papers thereunto annexed, are filed among the Records of Parliament; the Tenor of which Articles followeth, in these Words:

“It was then and there, (that is to say,) the said Tenth Day of July, by their Lordships Ordered, That the said John Lilbourne be brought to the Bar of this House the 11th Day of the said July, to answer the said Articles, that thereupon their Lordships might proceed therein according as to Justice should appertain; at which Day, scilicet, the 11th Day of July, Anno Domini 1646, the said John Lilburne, according to the said Order, was brought before the Peers then assembled and sitting in Parliament, to answer the said Articles; and the said John Lilburne being thereupon required, by the said Peers in Parliament, to kneel at the Bar of the said House, as is used in such Cases, and to hear his said Charge read, to the End that he might be enabled to make Defence thereunto, the said John Lilburne, in Contempt and Scorn of the said High Court, did not only refuse to kneel at the said Bar, but did also, in a contemptuous Manner, then and there, at the open Bar of the said House, openly and contemptuously refuse to hear the said Articles read, and used divers contemptuous Words, in high Derogation of the Justice, Dignity, and Power of the said Court; and the said Charge being nevertheless then and there read, the said John Lilburne was then and there, by the said Lords assembled in Parliament, demanded what Answer or Defence he would make thereunto; the said John Lilburne, persisting in his obstinate and contemptuous Behaviour, did peremptorily and absolutely refuse to make any Defence or Answer to the said Articles; and did then and there, in high Contempt of the said Court, and of the Peers there assembled, at the open Bar of the said House of Peers, affirm, “That they were Usurpers and unrighteous Judges, and that he would not answer the said Articles;” and used divers other insolent and contemptuous Speeches against their Lordships and that High Court: Whereupon the Lords assembled in Parliament, taking into their serious Consideration the said contemptuous Carriage and Words of the said John Lilburne, to the great Affront and Contempt of this High and Honourable Court, and the Justice, Authority, and Dignity thereof; it is therefore, this present 11th Day of July, Ordered and Adjudged, by the Lords assembled in Parliament, That the said John Lilburne be fined, and the said John Lilburne by the Lords assembled in Parliament, for his said Contempt, is fined, to the King’s Majesty, in the Sum of Two Thousand Pounds: And it is further Ordered and Adjudged, by the said Lords assembled in Parliament, That the said John Lilburne, for his said Contempts, be and stand committed to The Tower of London, during the Pleasure of this House: And further the said Lords assembled in Parliament, taking into Consideration the said contemptuous Refusal of the said John Lilburne to make any Defence or Answer to the said Articles, did Declare, That the said John Lilburne ought not thereby to escape the Justice of this House; but the said Articles, and the Offences thereby charged to have been committed by the said John Lilburne, ought thereupon to be taken as confessed: Therefore the Lords assembled in Parliament, taking the Premises into Consideration, and for that it appears by the said Articles that the said John Lilburne hath not only maliciously published several scandalous and libelous Passages of a very high Nature against the Peers of this Parliament therein particularly named, and against the Peerage of this Realm in general, but contrived, and contemptuously published, and openly at the Bar of the House delivered, certain scandalous Papers, to the high Contempt and Scandal of the Dignity, Power, and Authority of this House: All which Offences, by the peremptory Refusal of the said John Lilburne to answer or make any Defence to the said Articles, stand confessed by the said Lilburne as they are in the said Articles charged:

“It is, therefore, the said Day and Year last abovementioned, further Ordered and Adjudged, by the Lords assembled in Parliament, upon the whole Matter in the said Articles contained,

“1. That the said John Lilburne be sined to the King’s Majesty in the Sum of Two Thousand Pounds.

“2. And, That he stand and be imprisoned in The Tower of London, by the Space of Seven Years next ensuing.

“3. And further, That he, the said John Lilburne, from henceforth stand and be uncapable to bear any Office or Place, in Military or in Civil Government, in Church or Commonwealth, during his Life.”

This passage, taken from the ‘House of Lords Journal Volume 8: 17 September 1646’, and subsequently published in the Journal of the House of Lords: volume 8: 1645-1647 (1802), pp. 493-494, presents the reader with a number of interesting legal anomalies: which may well explain the attitude of the defendant. The first of which is that the entire trial appears to have been conducted in the King’s Name, much as modern day criminal trials still are, by members of the English Civil War Parliamentary faction at a time when they themselves were engaged in armed struggle with the self same monarch in whose name Lilburne had been brought to trial.

The other interesting anomaly involves the fact that at no point in the trial transcript is there any mention whatsoever of the affair for which Lilburne was originally arrested. Namely, the accusations he is reported to have made against the Earl of Manchester. Indeed, this entire tract is suggestive of the fact that Lilburne was in reality on trial first and foremost for his ideas. And in particular those ideas which he himself had previously committed to writing. His’England’s Birthright Justified‘, published in October 1645, at about the same time as he had previously been released from prison, for example, defends the rule of law against arbitrary power. In it Lilburne argues that Parliament’s own power must be limited by law to protect the rights of the individual. The author also attacks the monopolies of preaching, in the form of the Established Church and its Ministers, the Merchant Adventurers who dominated the Wool Trade, and the Stationers’ Company who controlled the printing of all published books.

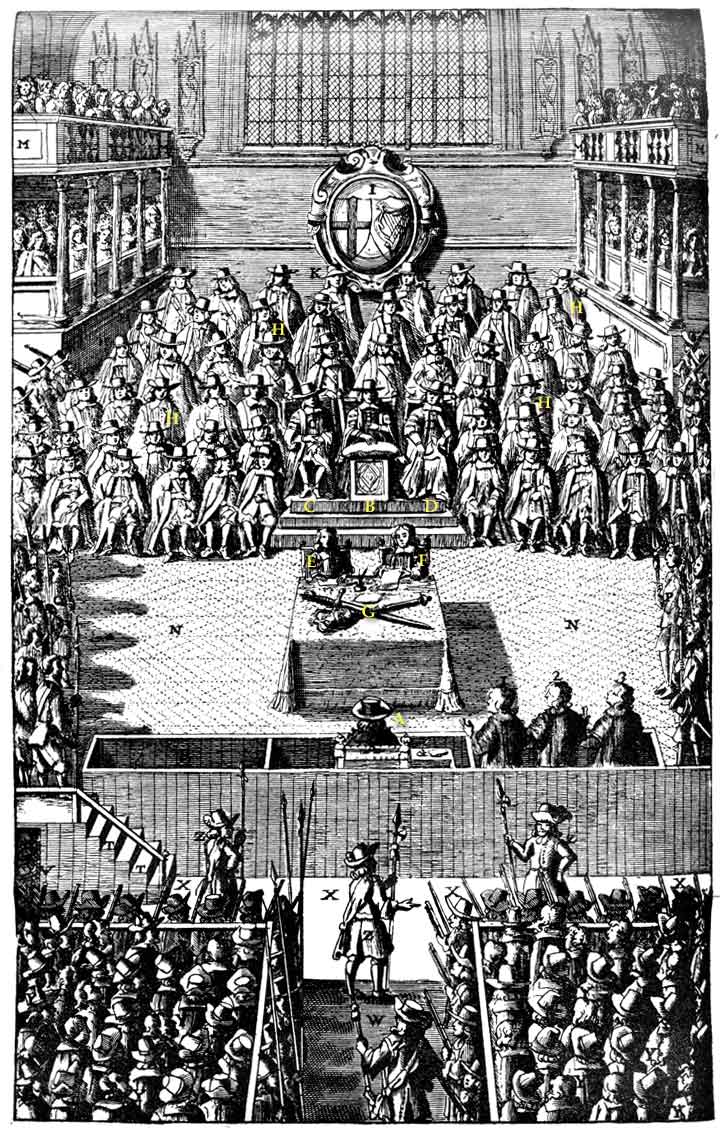

The subsequent campaign to free Lilburne from prison was to lead to the establishment of the entire Leveller Movement, including the political party of the same name. Following the spreading of false rumours that the Levellers, who wanted a complete end to the Monarchy and the House of Lords, were conspiring with the Royalists to overthrow the new republican government, which had come to be dominated by the landed classes, Lilburne himself was accused of incitement. On 26 October 1649 he was brought to trial yet again. This time at the Guildhall in London, where he was charged with high treason and with inciting the Leveller mutinies within the Army.

At his trial Lilburne spoke eloquently in his own defence: ‘Sir, will it please you to hear me? and if so, by your favour thus. All the privilege for my part that I shall crave this day at your hands, is no more but that which is properly and singly the liberty of every free-born Englishman, viz. The benefit of the Laws and Liberties thereof, which by my birthright and inheritance is due unto me; the which I have fought for as well as others have done, with a single and upright heart; and if I cannot have and enjoy this, I shall leave this Testimony behind me, That I died for the Laws and Liberies of this nation; and upon this score I stand, and if I perish I perish.’

Once again his was released from prison just as he had been on 14th October, 1645, this time after being acquitted by a jury. Of further interest is the fact that during his previous trial before the Lords it had been ruled that ‘the said John Lilburne be sined to the King’s Majesty in the Sum of Two Thousand Pounds’. This refers to a fine of £2000 that he had been ordered to pay on being found guilty.

The particular point of relevance here is that following his previous release from prison in October 1645, John Bradshaw, who would himself rise to prominence as President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I and as the first Lord President of the Council of State of the English Commonwealth, had brought a case before the Star Chamber on Lilburne’s behalf in the matter of a large sum of back pay that he should have received while serving as a Colonel in the Parliamentary Army. The sum that Lilburne was awarded as a result of this case, which amounted to some £2,000 in compensation for his sufferings, was never paid by Parliament and appears to have been at the heart of the later decision to arrest him in the affair of the Earl of Manchester. It is interesting to note then that the money he had been owed, and the sum he would later be fined, amount to precisely the same amount.

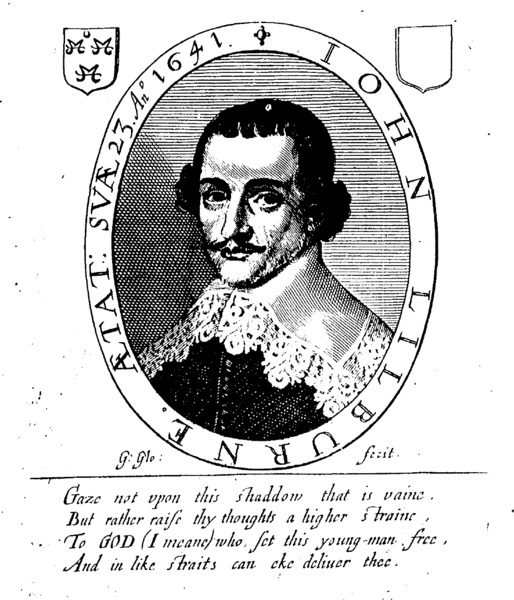

Picture Credit: John Lilburne: Wikimedia Commons Creative Commons Licence